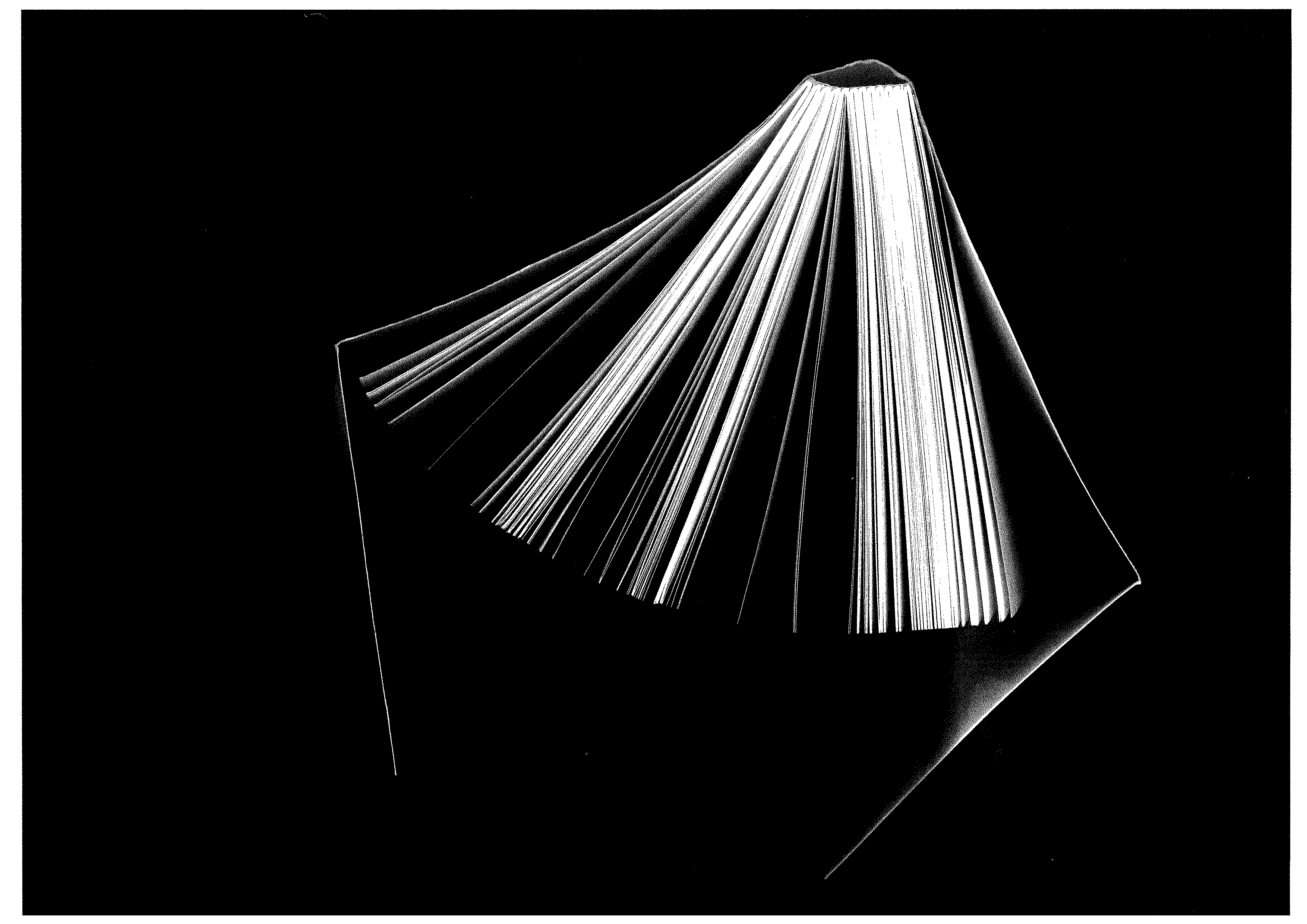

The materiality of a book as it is known today, paper, is an evolution from ancient materials: animal skin (parchment and vellum), Asian skill and Egyptian papyrus.

It was a Chinese chief eunuch called Cai Lun who in AD 105, determined to create a writ- ing surface less expensive than the silk then in use, experimented with mixtures of tree, cloth and silk until he produced sheets that resembled today’s modern paper.

Both these ancient and modern materials share one quality – they all absorb sound.A feature that is not given a lot of thought today but which played an important role for Cai Lun when he invented a new material for the object of the book.

In the days before silent reading became common, reading was an oral expression. Scholars did not rely on books as memory tools. The acquisition of knowledge was a personal pursuit. Each word had to be internalised, memorised by the reader.

One would find books amid the sweetness of honey and dried grapes. The consumption of twenty-one raisins a day was recommended to sharpen the skill of memorising. As well as that, one should avoid the consumption of coriander and eggplant, which were deemed deleterious.

The habit of spoken reading – usually accompanied by the beat of walking, as was customary in Greece – and the quest for knowledge required a high level of concen- tration. This need for an undisturbed mind was of high interest to Cai Lun. He sought for a material that could counteract the spoken word by absorbing its sound.

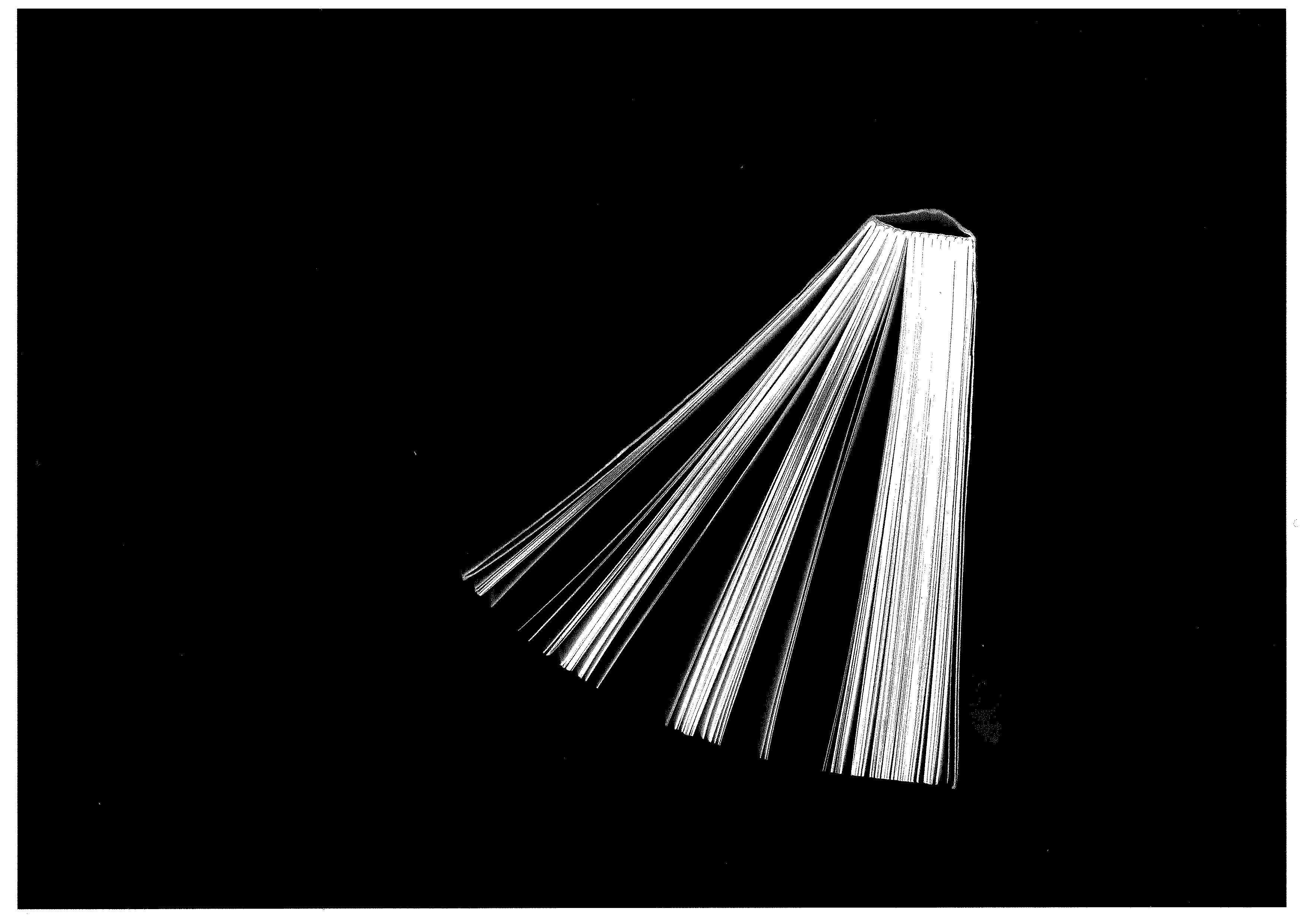

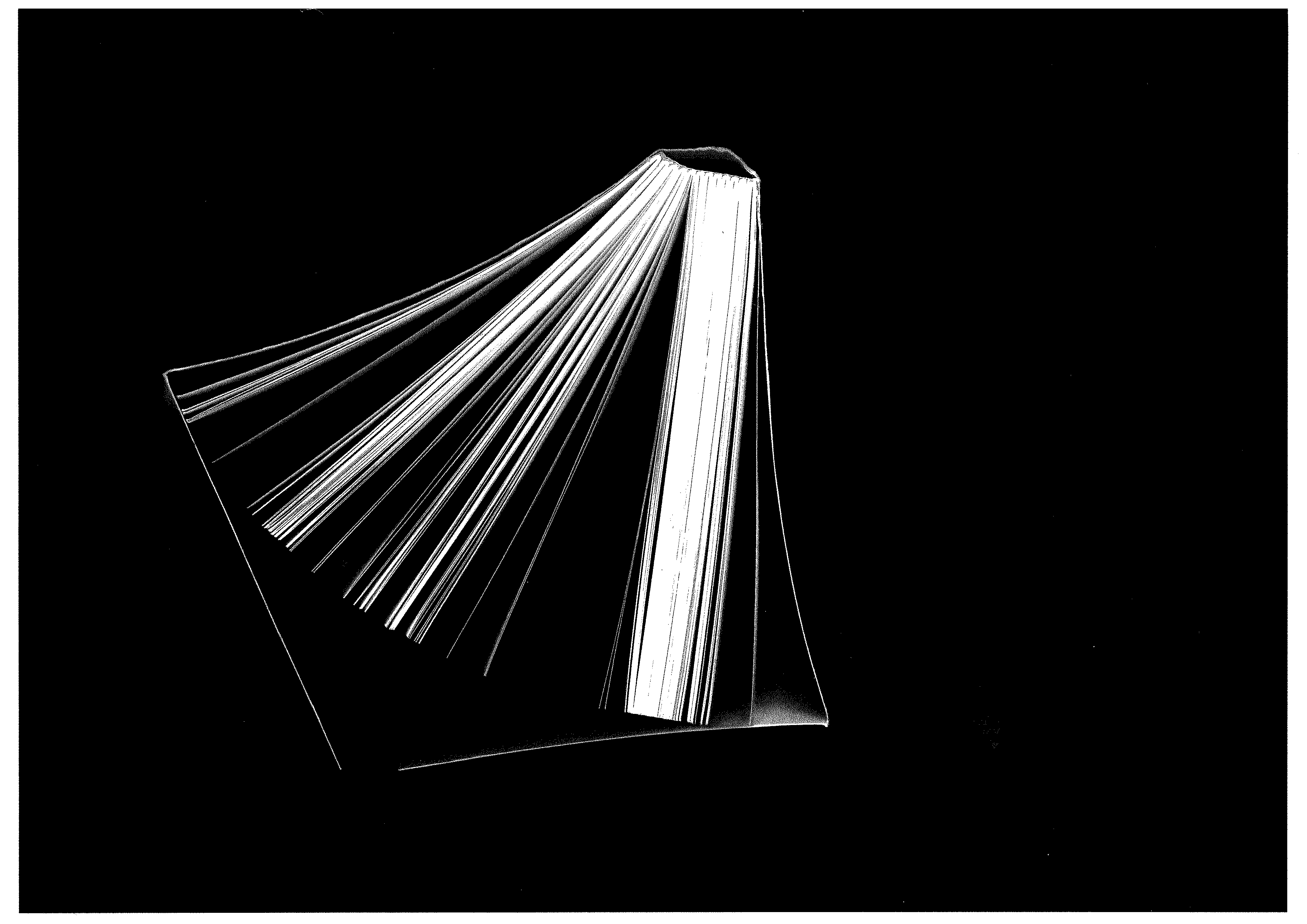

Reading is said to be a constant ritual of rebirth. It is the source of an ever-shifting present in which new readers engage with old books. As such every reader extends a given book a modest immortality. Reading aloud their words with contemporary voices they echo a new time and space, sometimes very far from its original creation, the book becomes anew.

Neither honey, raisins or communal (ambu- lant) mumbling surround the reader today. But the ghosts of these elements can be felt in the very fabric and design of the book,

if we look for it.

Books continue to be paper shields as origi- nally conceived, although noise is no longer the main threat for the concentrated reader.

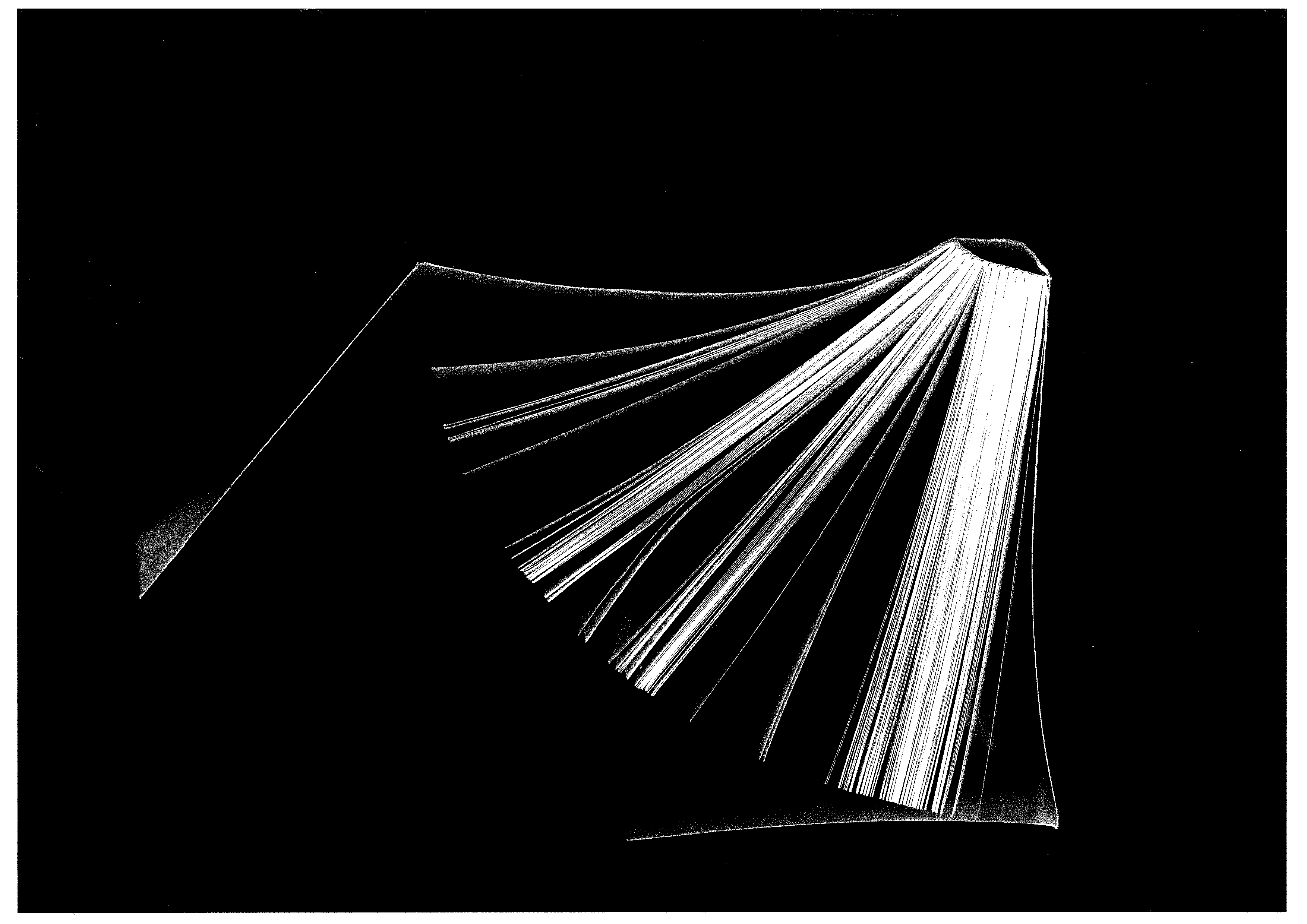

Today, readers fight to not be visually dis- tracted. The way our eyes capture informa- tion is not a steady action. Although words are laid out in straight lines, we never follow the suggested order. Three or four times per second, our pupils jump out of the pape page, and just in between that coming and going, on those breaks in between jumps, we actually follow and read the written lines.

The reason for this reading in motion is related to a sense of protection. We are the surviving descendants of hunters and gath- erers. We are always on alert, reacting to the slightest movement around us.

This natural inclination (a blessing that as- sured our existence until today) can also be seen as a curse. When technology is invading both private and public spheres, replacing the stillness and natural movement of land- scape with moving images and information in screens, our pupils are naturally attracted to them. Understanding the object of the book, its parts and reasoning, opens the door to adaptation and a response to contemporary needs.

[Edition of 10 monochrome prints]